As 2024 ends, we’ll look back a hundred years to one of the greatest discoveries of all time..

A century ago an American astronomer announced an astounding discovery.

In November, 1924, Edwin Hubble revealed the Big Universe.

Different Views

A century ago, many astronomers believed that our Milky Way was the entire universe.

All the stars, planets, star clusters and nebulae we could see were part of a big star city.

That was it. There was nothing else, nothing outside this huge collection of stars.

But other astronomers disagreed.

They maintained that the Universe was much larger than our Milky Way.

There were other ‘Milky Ways’ outside ours.

Galaxy Cluster: NASA / HST

The Great Debate

The argument came to a head at the Smithsonian Museum in Washington in April, 1920.

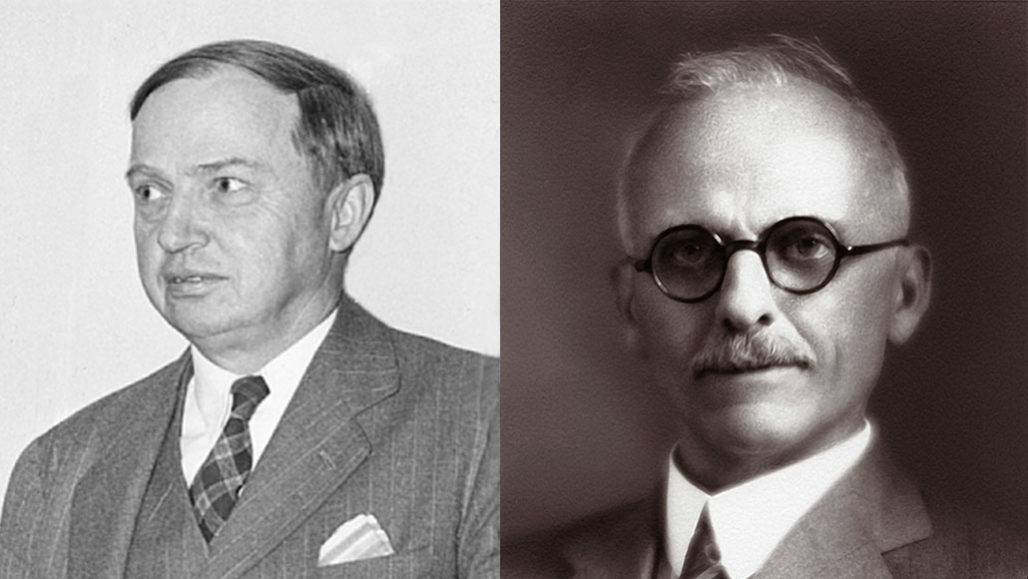

Astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis represented the opposing camps in the ‘Great Debate’.

Harlow Shapley Heber Curtis

The discussions hinged on the nature of ‘spiral nebulae’.

Shapley said that the ‘spiral nebule’ were within our Milky Way.

He presented evidence that the spirals were relatively small.

They were clouds of gas and dust in the outlying regions of the Milky Way.

Curtis propounded the opposing theory.

The spirals were in fact huge star systems at great distances beyond the Milky Way.

They were ‘Island Universes’, objects we now know as galaxies.

Settling the Argument

The resolution of the debate depended on measuring the distance of the spiral nebulae.

If they were close, within a few thousand light years, then Shapley was right.

The universe was just the Milky Way.

But if the spirals were hundreds of thousands of light years distant, Curtis was correct.

The spirals were ‘island universes’ far beyond the Milky Way.

But how could the distance be measured?

In fact the method was already available through the work of a wonderful female astronomer.

Henrietta Leavitt

Henrietta Swan Leavitt worked at Harvard College Observatory.

Her primary duty was to catalogue stars, their positions and brightness.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/swanleavitt-5aa1c5b56edd65003617e695.jpg)

Henrietta went far beyond this.

In 1912 she presented a paper which would solve the problem of measuring the distance to the spiral nebulae.

The paper involved Cepheid variable stars.

These stars changed brightness in a regular pattern.

Delta Cephei, the eponymous Cepheid variable star

But crucially Henrietta found that the time between peaks in brightness were related to the actual brightness of the stars.

The longer the period, the brighter the star.

So by measuring the time between brightness peaks, astronomers would know the true brightness of a star.

Then it was a simple task to compare the true brightness with the observed brightness.

The difference would give an accurate measure of the star’s distance.

All it needed was an astronomer to do it – and a big telescope to do it with.

The Telescope

In 1924 the largest telescope in the world was on Mount Wilson in California, USA.

Completed in 1917, it’s mirror was 100 inches across or 2.5 metres.

It would remain the world’s largest until 1949.

The 100-inch would finally settle the great debate with Edwin Hubble.

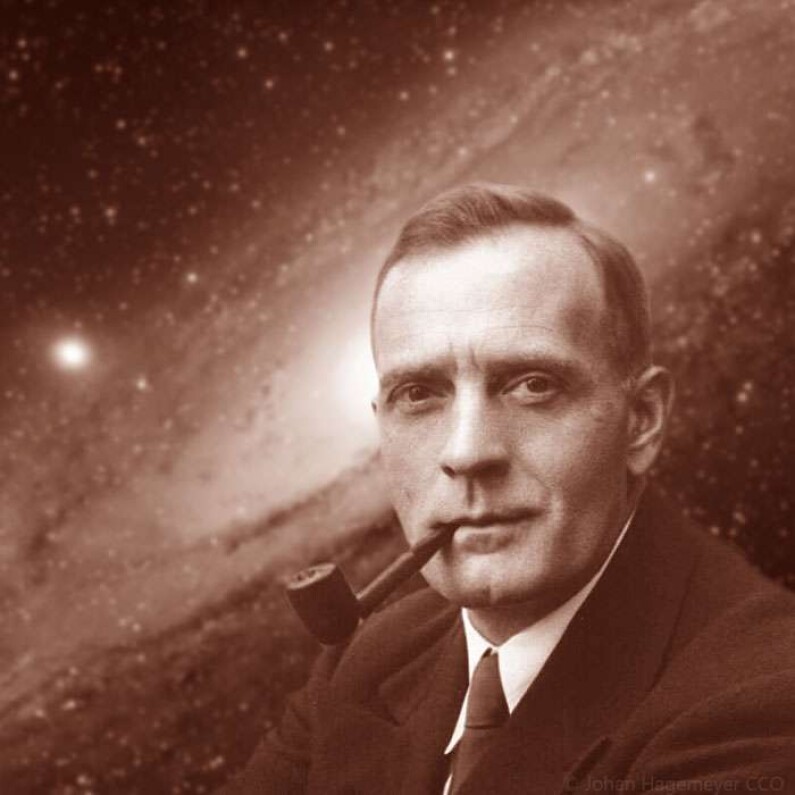

Edwin Hubble

Hubble joined the Mount Wilson staff in 1919.

He began searching for Cepheid variable stars in the Andromeda spiral, the brightest of these nebulae.

It was a difficult task. There are billions of stars in Andromeda.

It really was like looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack.

Starfield in Andromeda Spiral, NASA / HST

Eventually Hubble found a star which became brighter than normal.

He labelled it ‘N’ for Nova, a star with an outburst of light.

Hubble discovery plate

But the star dimmed and brightened again then repeated the regular pattern.

Hubble crossed out ‘N’ and excitedly scribbled in ‘VAR!’

It was a Cepheid variable star!

Andromeda distance

Hubble applied Henrietta Leavitt’s period-luminosity law to the star in Andromeda.

Hubble’s Cepheid in Andromeda: NSA / HST

Light curve of Cepheid variable star in Andromeda spiral

From its light curve, Hubble calculated the star’s true brightness – very bright.

He compared it with the observed brightness – very dim.

The difference in brightness was a measure of its distance.

It’s distance worked out to 860,000 light years.

That was more than 8 times the size of the Milky Way.

The Andromeda spiral was a separate star system far beyond our star system.

It was an ‘island universe’, a galaxy, a city of stars like our Milky Way.

Andromeda Galaxy,: ESA / HST

Hubble made his discovery on October 6th, 1923.

But he had to verify his findings.

He went on to find Cepheids in another nearby galaxy, the Pinwheel, M33.

It too measured about 1 million light years away.

M33, the Pinwheel galaxy in Triangulum. Credit NASA / HST

The debate was over.

The universe is a huge space populated by ‘star cities’ – galaxies.

It’s a Big Universe!

Recalibration

Hubble’s measurement settled the argument.

The universe is vast and contains billions of galaxies like our own Milky Way.

Hercules Cluster of galaxies: NASA / ESA / Webb

Since 1924 the Cepheid measurements have been recalibrated.

The true distance of Andromeda is now put at an even greater 2.5 million light years.

The Pinwheel is 2.73 million light years away.

And more to come

The discovery of the Big Universe was only the beginning of Hubble’s impact on astronomy.

A few years later he would make another astounding discovery.

We’ll feature the expanding universe in a future blog.

Look Out There

But for now we’ll reflect on Edwin Hubble’s first major achievement a century ago.

We can look out at the night sky this month into the vastness of space.

We are looking at the Big Universe.

The author: Dennis Ashton is a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society and a Wonderdome presenter.

In 2024, Dennis received the Special Contribution award from the British Association of Planetaria.

Would you like to hear more Astronomy news?

Do you want to to find out about our upcoming public events?

Follow WonderDome Portable Planetarium on Twitter and Facebook or go to our web site wonderdome.co.uk