Brave New Worlds

In a previous blog, I outlined how exoplanets are found.

It is difficult to detect exoplanets but even harder to discover their nature.

However astronomers can make educated guesses to what individual exoplants are like.

Their size and distance from the parent star can be measured.

This gives an estimate of what they are made from, their temperature and so on.

Using instruments attached to telescopes, astronomers can begin to assess their atmospheres and climate.

We’ll take a look at five exoplanets in more detail.

They are planets which may hold life or have unusual features.

It’s a trip to brave New Worlds.

Kepler 186f: alien life?

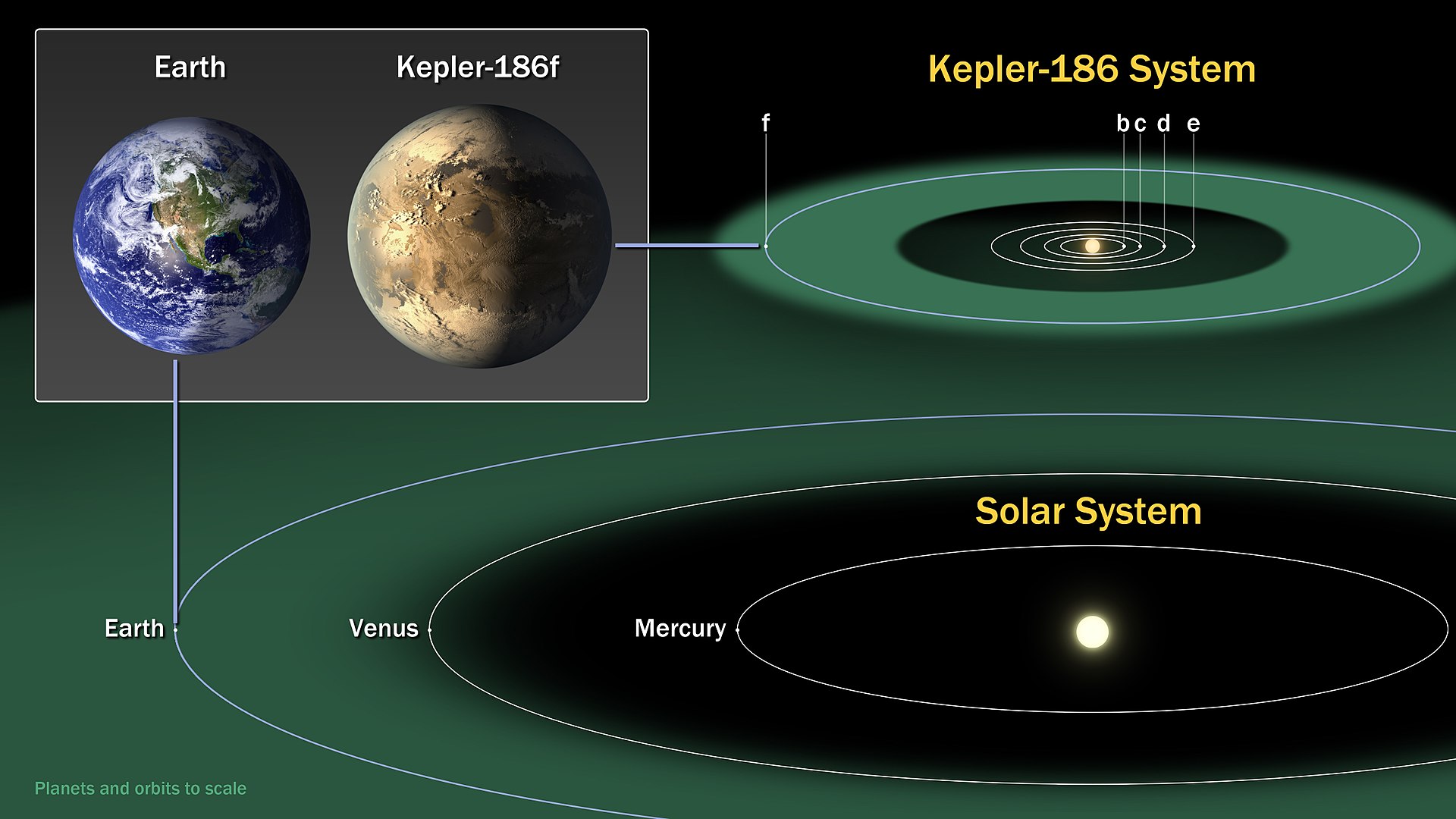

Exoplanet Kepler 186f was discovered by the Kepler Space Telescope in 2014.

Kepler 186f, artist impression. Credits: NASA Ames/SETI Institute/JPL-Caltech

It’s my first choice because it is the first discovery of an Earth-size planet in the habitable zone of a star.

Kepler 186 is a red dwarf star in the constellation Cygnus.

Kepler found 5 planets orbiting the star.

186f is the outermost of these planets.

It is a bit larger than Earth so likely to be a rocky planet.

It orbits around 60 million km from its star, a distance similar to Mercury from our Sun.

Because Kepler 186 is a dwarf star, it’s radiation is much less than our Sun.

Planet 186f is therefore in the habitable zone of its star.

The temperature may allow liquid water to exist on the planet.

With that water, there could be life.

Kepler 186 & planets. Credits: NASA Ames/SETI Institute/JPL-Caltech

Kepler 186 is around 580 light years away.

This is too far for our telescopes to detect an atmosphere.

If there is an atmosphere of some kind, the surface temperature should be above zero degrees Celcius.

There may be water there – and life.

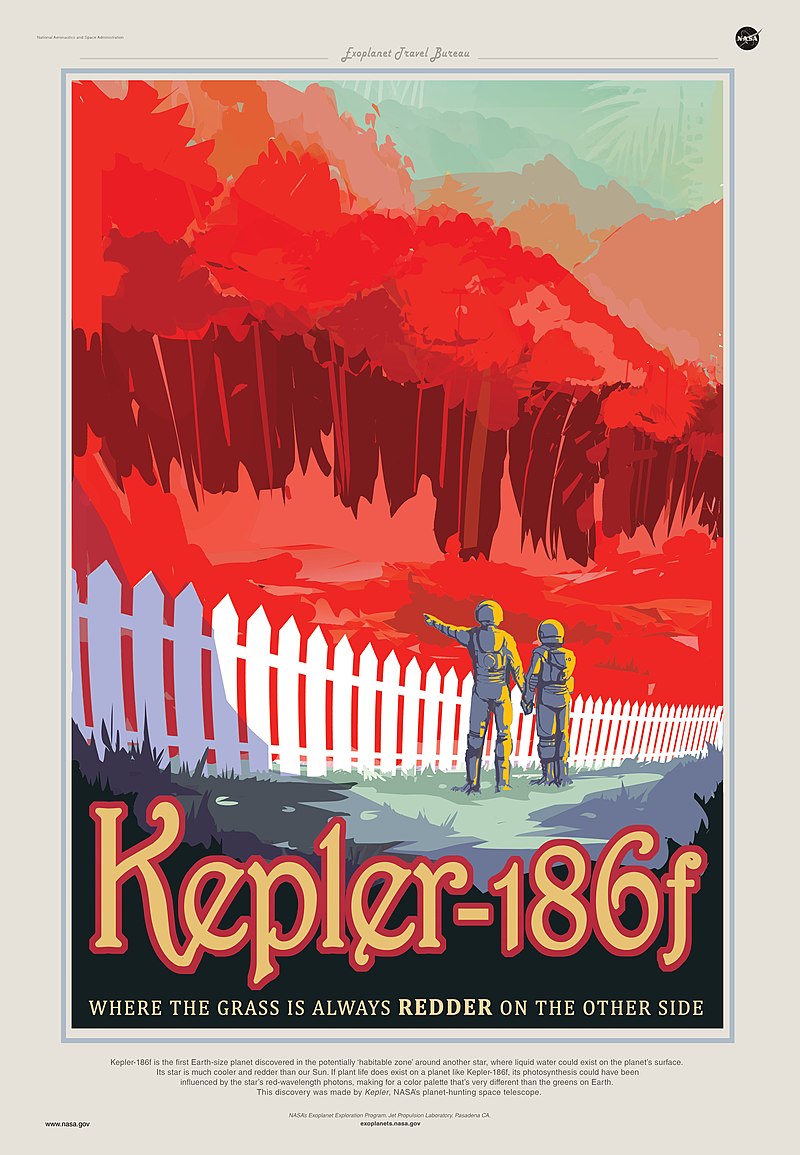

But, as this travel poster from NASA suggests, it may not be life as we know it!

Credit: NASA/JPL-CalTech

51 Pegasi b: Hot Jupiter

The first planet discovered orbiting a sun-type star orbits the star 51 Pegasi.

As the name suggests, it is in the constellation Pegasus.

It lies to the right of the constellation’s square, about 50 light years away.

51 Pegasi b, artist impression. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

The discovery in 1995 was ground-breaking.

The discoverers, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics.

However the nature of the planet was most unexpected.

51 Pegasi b orbits its star at a distance of only 8 million km.

This is far closer than Mercury is to our Sun.

It takes only four days to orbit – its year is just 4 days!

Even more surprisingly, 51 Pegasi b is a gas giant planet, at least 150 times more massive than Earth.

It is more similar to Jupiter than our planet.

It is a ‘hot Jupiter’.

Like many other astronomers, I was surprised at this.

Gas giant planets in our Solar System orbit far from the Sun.

This configuration was expected for exoplanets.

So at first we thought that 51 Pegb would prove to be unusual.

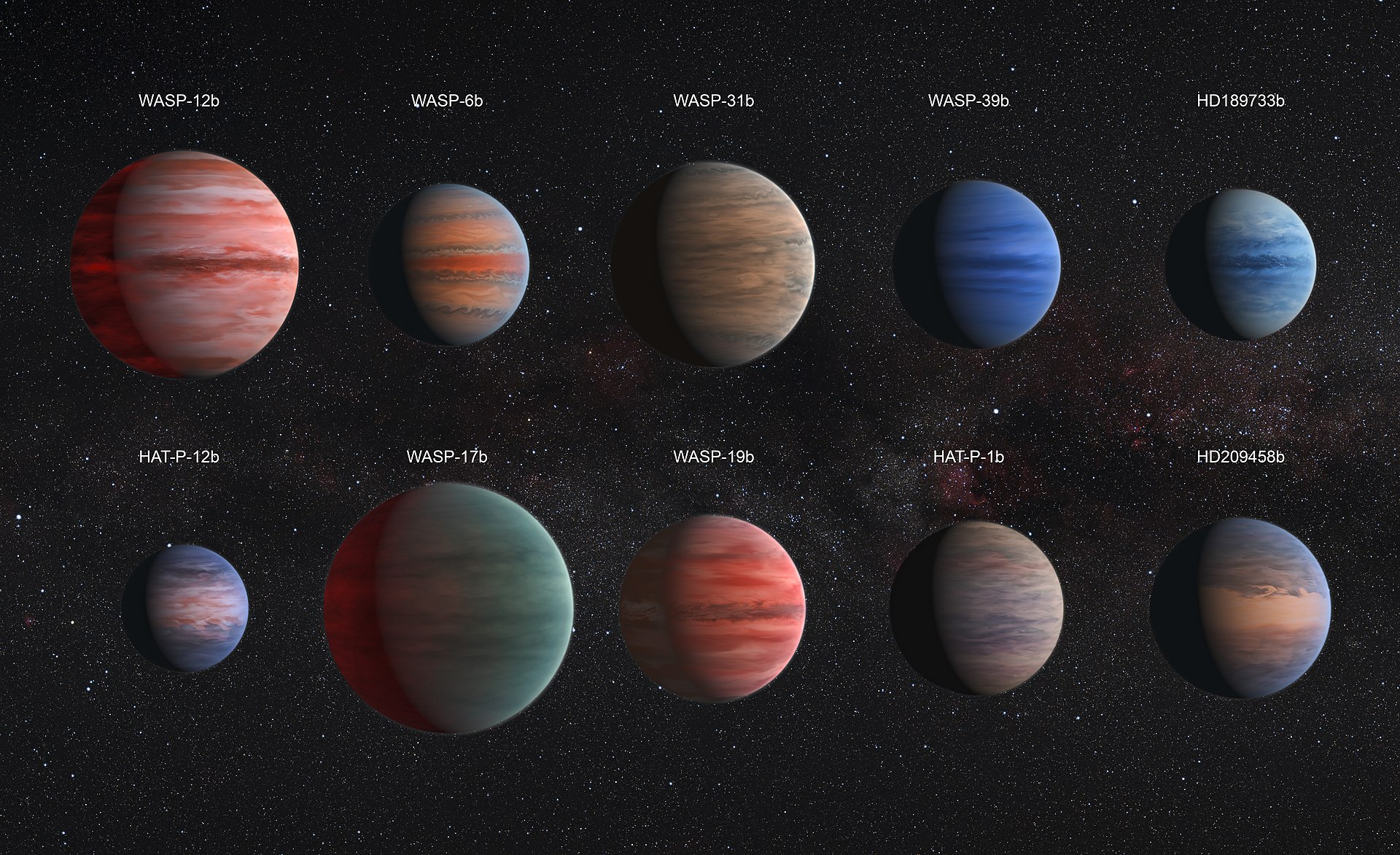

But many other ‘hot Jupiters’ have been found.

Perhaps we’ll have to reconsider how planetary systems are formed.

Maybe our gas giants formed nearer to the Sun then migrated outwards.

Hot Jupiters, artist impression. Credit: ESA/Hubble

The ESA/Hubble image shows some hot Jupiters.

They are relatively easy to find because they have quite a significant gravitational effect on their parent star.

The star ‘wobble’ is greater than smaller, more distant exoplanets.

WASP is the Wide Angle Search for Planets.

It involves two robotic telescopes.

One is on La Palma, the other is in South Africa.

WASP 76b: Iron Rain

Our next planet is a WASP discovery.

WASP 76b is an exoplanet in orbit round a star in the constellation Cetus.

It is a hot Jupiter, tidally locked with its parent star.

This means that one side of the planet permanently faces the star.

The other side is in perpetual night.

On the starlit side, the temperature is around 2,500 C.

This is hot enough to vapourise iron!

The dark side is still fiendishly hot, around 1,500 C.

When winds carry iron vapour from the hot side to the cooler hemisphere, it rains iron rain!

Iron rain on WASP 76b. Credit: ESO/ M.Kormnesser

HD 189733b: Raining Glass

Raining material like iron maybe extreme but it is not unique.

On our next planet it rains molten glass!

HD 189733b orbits a star in Vulpecula, some 65 light years away.

It’s a hot Jupiter, orbiting its star at a distance of only 4.5 million km.

It speeds around the star at 340,000 mph in just two days.

HD 189733b, artist impression Image Credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser

The spectrum indicates that HD189733b is bright blue in colour.

This beautiful blue appearance belies the planet’s true nature.

The weather is deadly.

Winds blow at over 5.000 mph.

The heat turns silicate particles into glass.

The winds blow glass rain horizontally across the face of the planet.

HD 189733b is not a welcoming world!

Kepler 22b: Waterworld

The star Kepler 22 is a sun-like star in the constellation Cygnus.

Exoplanet 22b is about two-and-a -half times bigger than Earth.

It orbits the star every 290 days at a distance about eight-tenths Earth distance from the Sun.

This puts it comfortably in the habitable zone, the area where liquid water can exist.

And water may be the hallmark of Kepler 22b.

Early studies indicate that the planet may have a rocky core surrounded by a liquid shell.

If that liquid is water, then 22b is a waterworld, a planet completely covered by ocean.

In that ocean there could be aquatic alien life.

Kepler22b, artist impression. Credit: NASA/Ames/JPL-Caltech

Planets, Jim, but not as we know them!

We can see from these five examples that these new worlds are very different from those in our Solar System.

Exoplanets come in a huge range of sizes, composition and orbits.

Many are deadly worlds where life could not develop.

But there are a few that hold the tantalising possibilty of extra-terrestrial life.

We’ll return with some more amazing exoplanets in a future blog.

The author: Dennis Ashton is a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society and a Wonderdome presenter.

Would you like to hear more Astronomy news?

Do you want to to find out about our upcoming public events?

Follow WonderDome Portable Planetarium on Twitter and Facebook or go to our web site wonderdome.co.uk