Exoplanets

Exoplanets are planets in orbit around stars other than our Sun.

Their discovery is one of the great advances in astronomy in recent years.

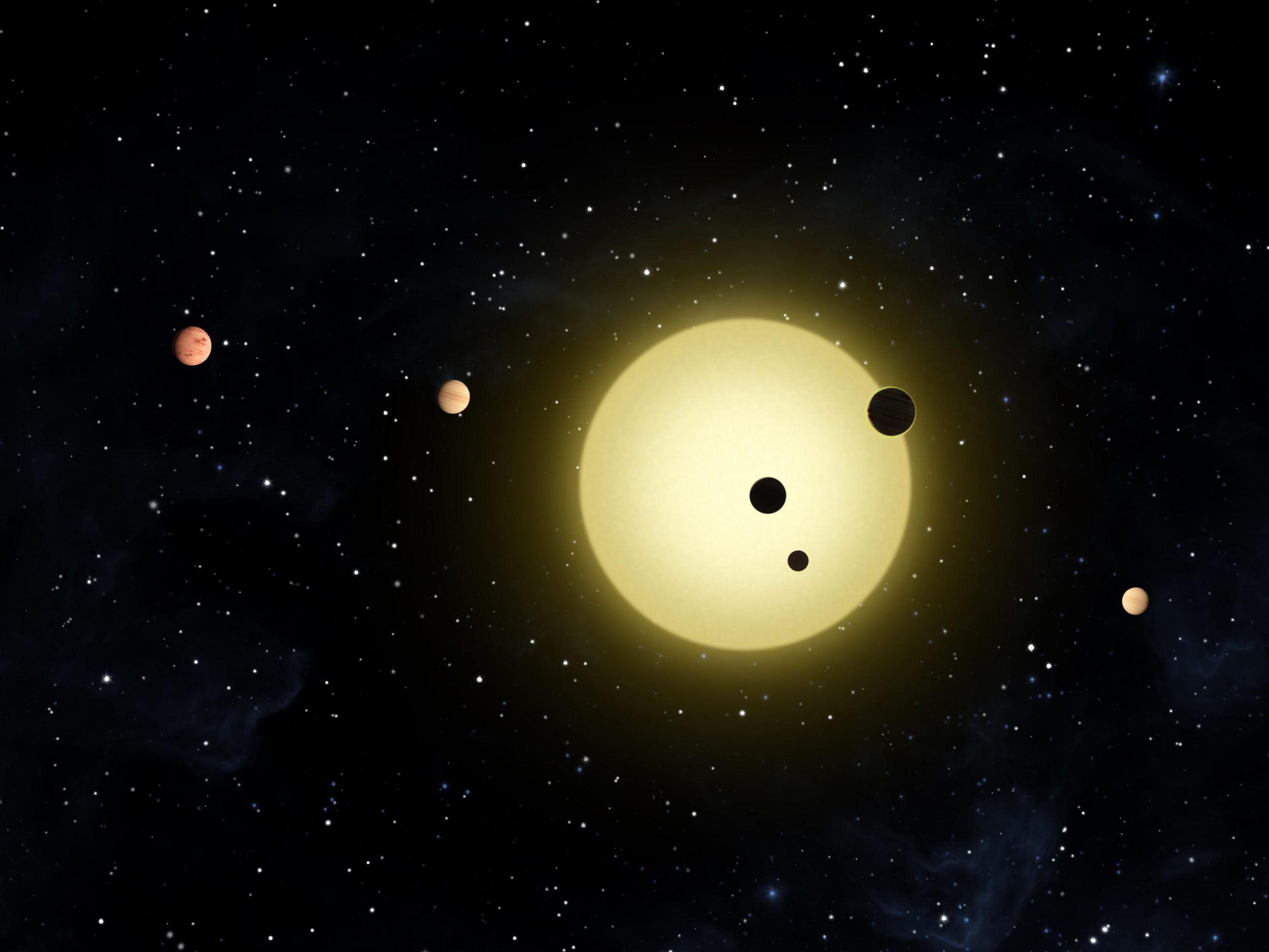

Kepler 11. Credit: NASA

Finding these distant worlds is not easy.

The planets are relatively small and very far away.

They are inherently dim objects.

They only reflect a little light from their parent star.

And the light from that star overwhelms that planetary illumination.

It’s like looking for a needle in a blazing haystack.

So how do we find these elusive worlds?

In this blog we’ll take a look at how exoplanets are detected.

How many exoplanets are there?

At the time of writing this blog, 5,445 exoplanets have been confirmed.

Another 9,714 are awaiting confirmation.

There are 4,196 planetary systems: some stars have more than one planet in orbit.

By the time you read this blog, the numbers will have increased.

New exoplanets are detected daily.

You can find today’s numbers at NASA’s Exoplanet Catalogue.

First Discoveries

The first exoplanet was discovered in 1992.

It is in orbit around a pulsar, the remains of an exploded superstar.

The system lies in the constellation Virgo.

The first planet found in orbit round a mainstream star was detected in 1995.

It orbits the star 51 Pegasi. to the right of the Square of Pegasus.

51 Pegasi is relatively close, some 50 light years away.

Planet orbiting 51 Pegasi, artist impression. Credit: NASA

Astronomers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz made the discovery using a telescope in France.

They were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2019.

The nature of 51 Pegasi is remarkable.

It is about half the size of Jupiter and orbits close to its star in only 4 days.

Space Telescopes

Exoplanets like 51 Pegasi can be detected using Earth-bound telescopes.

However space telescopes have a much clearer view.

Several are dedicated to finding exoplanets.

The first was Kepler.

It operated from 2009 to 2018 and found 2,662 exoplanets.

Kepler Space telescope. Credit: NASA

Kepler’s successor is TESS, the Transiting Exoplanet Survey satellite.

Still in operation, TESS has found around 300 exoplanets.

Another 5000 or so are awaiting conformation.

TESS Credit: NASA

The James Webb Space Telescope is not a dedicated planet finder, it has a wider brief.

However it has infra-red detectors which are ideal for finding exoplanets.

Artist impression of a Neptune-like planet discovered by Webb. Credit:NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC)

Discovery methods

Astronomers use a variety of clever ways to find exoplanets.

Very few of these distant worlds can be seen and photographed directly.

So astronomers use indirect methods of revealing their existence.

Wobbly Stars

A star holds a planet in orbit with its gravity.

The planet also has a small gravitational pull on its star.

The effect is to make the star wobble slightly.

By detecting a wobble, astronomers can infer the existence of an unseen planet.

Astronomers use a spectroscope to detect the wobble.

It’s called the Radial Velocity method.

Radial Velocity & exoplanets. Credit: Las Cumbrese Observatory.

The spectroscope shows starlight as a rainbow spectrum.

Elements in the star absorb light and produce dark lines.

Each element has its own barcode.

As a star wobbles, it causes the lines to move along the rainbow of colours.

To the blue, the star is coming towards us. Lines moving to the red indicate the star is moving away.

This is the Doppler Effect.

So find a wobbly star and it has a planet going round it.

51 Pegasi was discovered using this technique.

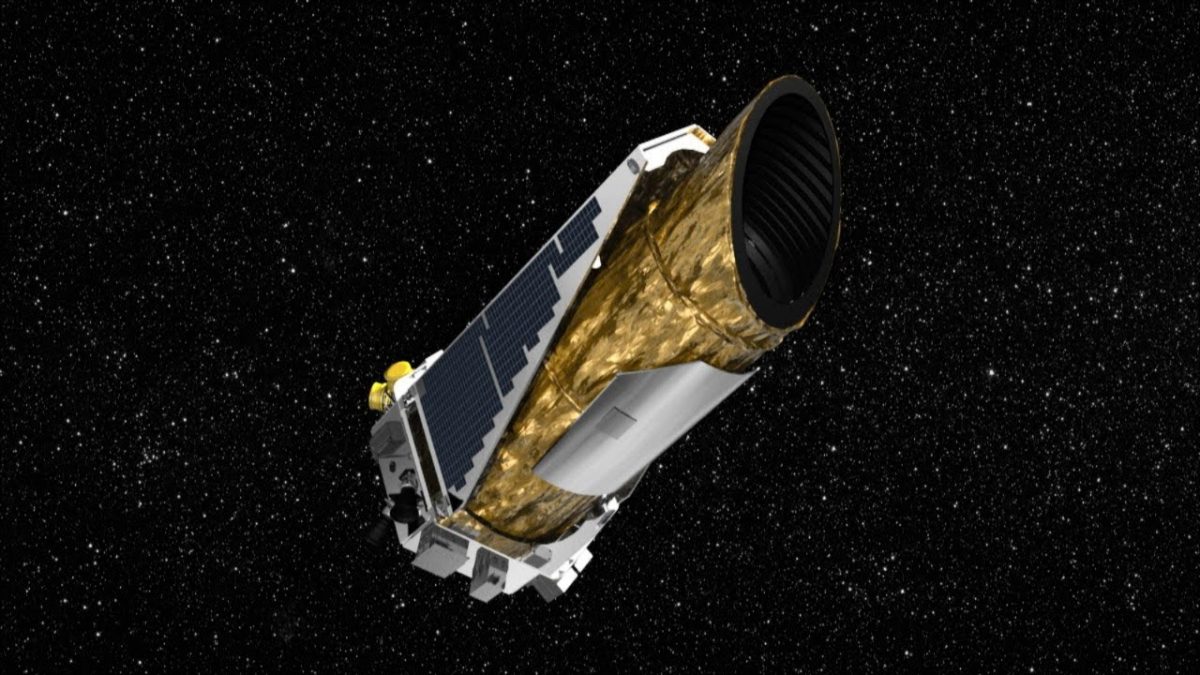

Transit Method

This is the most effective way to find exoplanets.

Kepler employs this technique but is so sensitive it can work with ground-based telescopes.

However it has limitations.

It depends on a planet passing in front of its star, seen from Earth.

Only about 10% of exoplanets fall into this fortunate category.

When a planet crosses in front of the star, it blocks out a little of the starlight.

When it moves away, the starlight goes back to normal.

Plotted on a graph, the data produces a distinctive light curve.

Exoplanet light curve. Credit: NASA, ESA, G.Bacon (STSci)

The pattern repeats regularly as the planet orbits the star.

The dimming is very small, maybe 1/100,000 of the normal starlight.

The TESS mission uses the transit method.

Other Methods

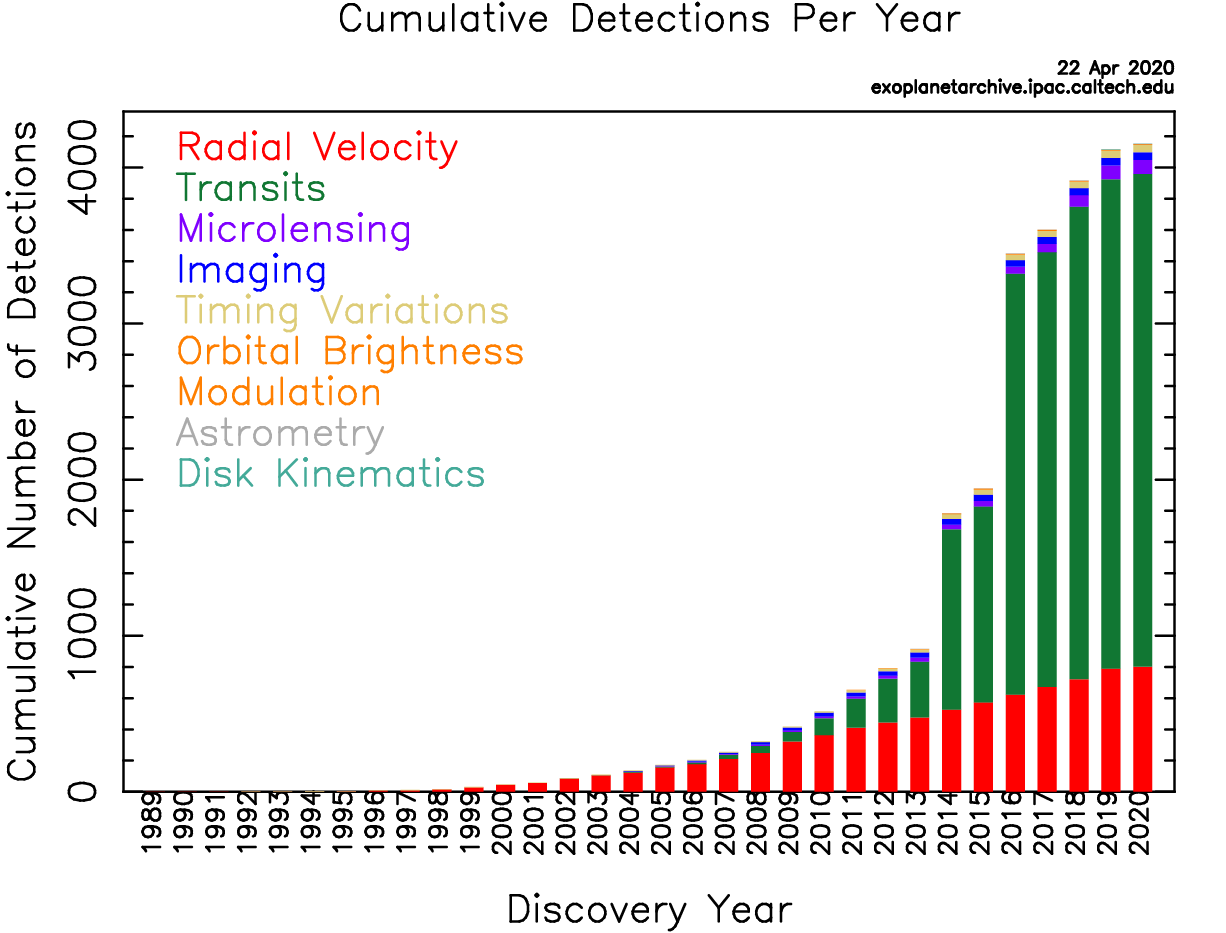

The graph below indicates that we find most exoplanets using these two techniques.

There are other indirect ways, as the graph below indicates.

We aren’t going to explore these now but you can find information here.

Annual discovery of exoplanets. Credit: caltech

The graph also shows how our discoveries have grown over the last 20 years.

Finding distant worlds is one of astronomy’s great success stories.

Direct Imaging

Star CVSO30 & exoplanet Credit: ESO/ Schmidt et al

Our picture shows a planet in orbit around its star – a real image of a real world.

The planet was first found by the transit method.

Following this, ESO’s Very Large telescope (VLT) in Chile took the image.

The system is close to the belt in Orion.

The star in the centre is a very young one, at the beginning of its life.

The planet is inside the red ring.

The planet, CVSO 30b, orbits only 2 million miles from its star.

It goes around in just 11 hours – a year in 11 hours!

Exoplanet Names

So far I’ve mentioned several exoplanets but named none of them.

That’s because they don’t have names. Well, not proper first names.

They are simply given letters after the name or number of their star.

For example, a star in the constellation Cancer is known as 55 Cancri.

It has five planets in orbit round it.

They are 55 Cancri b, 55 Cancri c, 55 Cancri d…….well, you get the idea.

This is all rather prosaic but recently the International Astronomical Union responded to some pressure.

They launched a scheme called NameExoWorlds, where a worldwide public vote could name some exoplanets.

Different countries were given different stars.

Three rounds have so far taken place, with around 80 stars receiving names.

Among them, perhaps predictably, are notable astronomers.

They include Galileo, Brahe, Lippershey and Harriott.

The Lichtenstein choice was ‘Poltergeist’, which I find quite appropriate for an elusive world of mystery.

You can see the full list here.

Alien Life?

A number of exoplanets lie in the habitable zone of their star.

These planets may have liquid water, which raises the possibility of life there.

That’s the theme of a future blog.

Kepler 186f Credits: NASA Ames/SETI Institute/JPL-Caltech

An Exoplanet Taster

That’s all we have time for now.

In a future blog, I’ll look at a selection of exoplanets.

We’ll look at some of the most bizarre and some that may harbour life.

In the meantime, here’s a fictional exoplanet that I think should exist.

Planet Vulcan. Credit: NASA

When Gene Roddenberry wrote ‘Star Trek’, he invented a character called Spock.

Spock came from the planet Vulcan, in orbit around the star 40 Eridani.

It lies below and right of our constellation Orion and around 16 light years away.

40 Eridani is a triple star system so Spock’s world has three Suns.

Does Vulcan really exist?

So far ….sadly no.

We have not found an exoplanet at 40 Eridani.

But there ought to be – and if we find one, it’s already got a name!

The author: Dennis Ashton is a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society and a Wonderdome presenter.

Would you like to hear more Astronomy news?

Do you want to to find out about our upcoming public events?

Follow WonderDome Portable Planetarium on Twitter and Facebook or go to our web site wonderdome.co.uk