The Leonid Meteors

‘It looked as though every star in the heavens was falling.’

In a recent blog we looked at meteors, shooting stars.

I mentioned meteor showers.

The Leonid meteor shower arrives in mid-November each year.

In the past the Leonids have become a meteor storm.

Origins

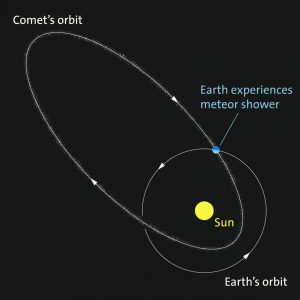

The Leonid meteors originate in dust left in space by Comet Temple-Tuttle.

Temple-Tuttle orbits the Sun every 33 years, a short period comet.

Comet orbit & Meteor shower. Credit: Griffith Observatory

This comet has a retrograde orbit, it travels in the opposite direction to Earth.

So when the dust particles hit the Earth’s atmosphere, they collide at great speed.

The dust enters our atmosphere at 160,000 miles per hour.

When the dust particles hit our atmosphere, they give the fastest moving of all shower meteors.

But that’s not the really unique feature of the Leonids.

Sometimes the shower turns into a meteor storm!

1833

Normally the Leonids produce around 15 meteors per hour.

There’s nothing remarkable other than their speed.

The peak date is in mid-November.

On November 12/13th, 1833 all that changed.

In North America the Leonids produced a meteor storm!

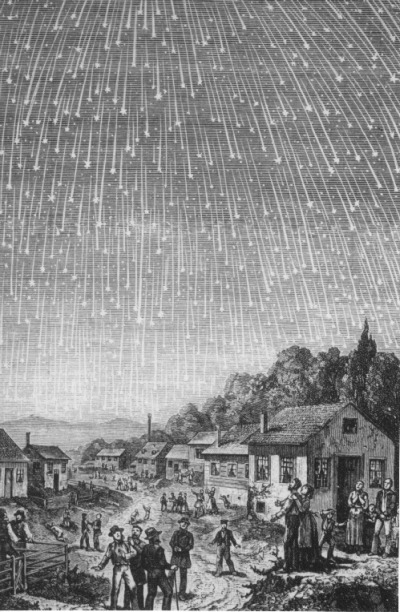

Leonids, 1833

This famous illustration gives some impression of that amazing night.

Over 100,000 shooting stars burst through the sky in a single hour.

In all, 250,000 meteors were seen that night.

An eyewitness reported that

‘The stars showered down so thickly and fast that it looked as though every star in the heavens was falling.’

The spectacle was made more intense because there was no Moon that night and, of course, no bright street lights.

The storm lasted nine hours and was seen all over North America east of the Rocky Mountains.

It made news all around the world.

It also stimulated research into meteors.

Explanation

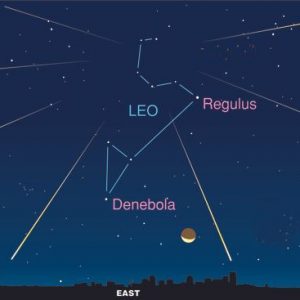

The best research was done by Denison Olmsted.

He noted that the shooting stars came from the direction of the constellation Leo.

He theorised that the storm was due to a narrow stream of particles.

They trailed in space between the planets.

These particles had entered the Earth’s atmosphere from the direction of the stars of Leo.

Leo radiant. Stardate magazine

It was the first time that anyone had worked out that meteors came from outer space.

Olmsted also suggested that the meteor dust was left in space by an object passing by the Earth.

The object must disintegrate and leave debris in its wake.

When Earth hits the debris, we see shooting stars.

That object, it was soon realised, was a comet.

Further discoveries

Historical research revealed that the 1833 storm was not unique.

The Chinese had recorded a storm in November 902AD, when ‘stars fell like rain‘.

In 1799, German scientist Alexander von Humboldt reported that in Venezuala

‘“…thousands of fireballs and falling stars fell in a row for four hours, often with a brightness like Jupiter.’

Humboldt heard from locals that a similar event had occurred in 1766.

Every 33 years

1766…1799….1833.

A meteor storm every 33 years. But Why?

The answer came in 1865 when Wilhelm Temple and Horace Tuttle independently discovered a comet.

Comet Temple-Tuttle is the source of the Leonids.

The comet orbits the Sun every 33 years.

It refreshes the debris trail with each passage.

So that every 33 years the Earth encounters a cloud of new meteor dust.

The result is a meteor storm every 33 years.

Or is it?

Since 1833

In 1866, right on cue, the Leonids produced another storm.

This time Europe saw the specatcle.

However it was not on the scale of 1833.

Around a thousand meteors per hour blazed across the sky.

There were repeats in 1867 and 1868 as we encountered different meteor streams from Temple-Tuttle.

Next came 1899….and nothing happened! No meteor storm.

On to 1933. No meteor display to speak of.

People forgot about the Leonids.

1966

Then in 1966 they were back.

Leonids 1966. Credit: D McLean, Kitt Peak. (RAS photo no. 697.)

On November 18th, 1966, North America was once again treated to an amazing Leonid storm.

In Texas, an observer said that

‘meteors falling in all directions gave the impression of a “gigantic umbrella,” appearing to “waterfall” out of the head of Leo.’

Later in California, an eyewitness reported

‘We watched a rain of meteors, turn into a hail of meteors and finally a storm of meteors, too numerous to count.’

At Kitt Peak in Arizona, amateur astronomers estimated they saw 40 meteors every second.

That’s 144,000 per hour!

What a sight that must have been.

New Predictions

We now know that the 1966 storm was caused by the passage of Comet Temple-Tuttle in 1899.

By the second half of the Twentieth Century, astronomers were able to map the dust trails left by comets.

We could now get predictions of enhanced meteor displays, even storms.

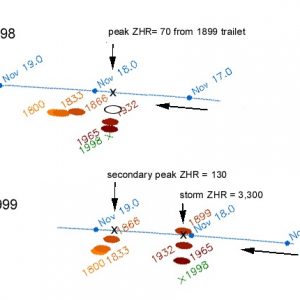

Remarkable work has been done by David Asher of Armagh Observatory and Robert McNaught of Siding Springs in Australia.

They plot the position of meteor streams for each passage of the comet.

Then they compute the drift of the streams due to the gravitational pull of planets.

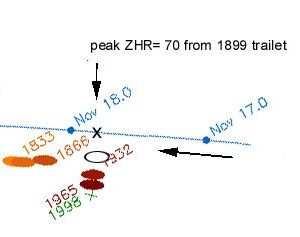

They produce a chart like the ones below for 1998 and 1999.

It shows the location of thick trails of comet debris and the passage of Earth through them.

Leonid dust trails and earth orbit. Credit: Asher & McNaught

The charts showed that 1998 would bring nothing special.

But 1999 would.

Then we would crash through debris left from the 1899 passage of Comet Temple-Tuttle.

The Leonid meteors could be back in storm force!

1999

The predictions were correct.

In Europe and the Middle East, observers with clear skies saw a storm.

The peak came around 2am on November 18th, with around to 70 meteors per minute.

That’s an hourly rate of 4,200, well into storm proportions.

1999 Leonids. Credit: NASA/Ames Research Center/ISAS/Shinsuke Abe and Hajime Yano

That night I observed from North Yorkshire with colleagues Steve Ibbotson and Andy Green.

Steve, Andy, Dennis. Malham, November 18th, 1999.

We camped near Malham Cove. It was very cold!

And unfortunately it was cloudy.

We sat near our tents staring at the cloud-covered sky.

Malham, North Yorkshire, November 1999.

It was very frustrating, particularly because we occasionally saw flashes of light in the clouds.

Meteors were burning across the sky but we couldn’t see them!

Around 2am the sky cleared for a few minutes.

Then we saw a flurry of shooting stars.

They weren’t very bright but numerous enough to tell of impressive Leonid activity.

2000 & 2001

Asher and McNaught predicted Leonid storms in 2001 and 2002.

In 2001 we encountered dust from 1767 and 1866.

Dust lanes, 2001. Credit: Asher & McNaught

The result was a 2000 storm in the Americas.

In 2001, western states of the USA and Hawaii saw lots of Leonids.

You can find images of the 2000 storm at Space Weather.

The Future

You will have worked out by now that the next Leonid storms are due in 2033 / 2034.

Although they may not reach storm force, 1,000 per hour, they may be spectacular.

In 2033 we may again encounter dust from Temple-Tuttle left in 1899.

We might see over 100 meteors per hour on November 17th.

2034 sees us pass through dust from the 1932 passage of the comet.

Again, we may see more than 100 shooting stars per hour.

I hope that I’m still alive to see them!

Fireball Night!

The Asher-McNaught chart for 1998 seemed to promise little Leonid activity.

However three of us from Sheffield Hallam University’s Star Centre decided to observe the shower.

It was really a dress rehearsal for the following year, the predicted Leonid storm of 1999.

So myself, Steve Ibbotson and Paul Crowder set up our tents at Malham Cove.

1998 Leonid expedition, Malham Cove with ducks.

That night defied predictions.

It turned out to be the best observing night of my life.

It was the Night of the Fireballs!

I’ll tell you what happened in my next blog.

Don’t miss it!

The author: Dennis Ashton is a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society and a Wonderdome presenter.

Would you like to hear more Astronomy news?

Do you want to to find out about our upcoming public events?

Follow WonderDome Portable Planetarium on Twitter and Facebook or go to our web site wonderdome.co.uk