Shooting Stars

Shooting stars, meteors, add unpredictable excitement to the night sky.

A meteor shower can be a entertaining event.

Super bright meteors, fireballs, can live long in the memory.

With a number of meteor showers coming up, we’ll take a look at these often spectacular sights.

Origins and appearance

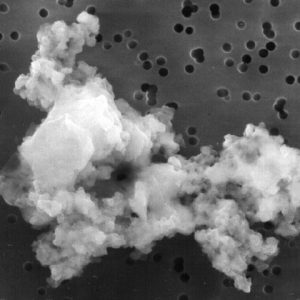

Meteoroids, space dust

Shooting stars are not stars falling from the sky.

A meteor is caused by a small piece of space dust, a meteoroid, hitting the Earth’s atmosphere.

For shorthand, we often say the dust particle ‘burns up’.

The truth is not quite so simple.

Space dust floats around between planets in the Solar System.

Each dust particle is the size of a grain of sand or smaller.

Space dust: micrometeorite

This dust can cause random meteors, called sporadics.

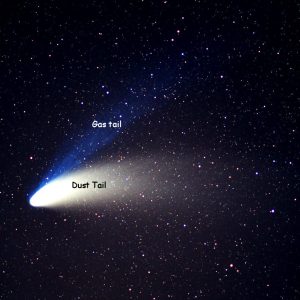

Space dust is also left in the wake of comets, the remains of a dust tail.

Comet Hale-Bopp showing gas tail & dust tail.

This concentrated dust can cause a meteor shower.

Then a number of meteors can be seen during a night.

They all come from the same point in the sky.

Speed

A fragment of space dust hits the atmosphere at great speed.

Typical meteor speeds are around 45,000 miles per hour.

At this speed, the particle becomes hot and begins to glow.

The glow begins about 100 km high.

Meteor from ISS NASA/ Ron Garan

The passage of the particle ionises the air, stripping atoms of their electrons.

A tiny tube of hot, glowing, ionised gas gives the trail and the appearance of a falling star.

Perseid meteor

Duration

Shooting stars last for a second or two.

But bright meteors leave a train of light that can persist for a while.

The slim tube of ionised gas can last for several minutes.

If it lasts long enough, the meteor train can change shape with high level winds before fading away.

Meteor train

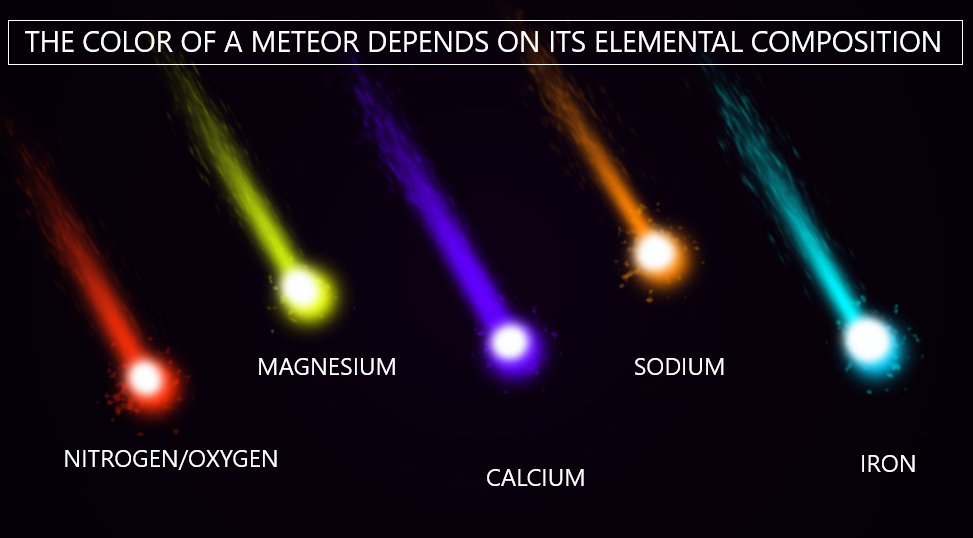

Colour

The colour of a shooting star depends on the composition and speed of the dust particle.

Elements in the meteor dust are like those used to give fireworks their colour.

Meteor colours. Credit: La Notte Stellata

Radar Detection

Meteors are visual objects, we can see them with the naked eye.

They can also be tracked by radar.

A radio signal can reflect from the ionised gas to be detected by a radio receiver.

In this way, meteors can be observed in cloudy conditions and in daytime.

Meteor Showers

When the Earth passes through a through a trail of old comet dust, we see a meteor shower.

The usual rate for random sporadic meteors is around 5 or 6 an hour.

In a shower the number increases to maybe 20 per hour, sometimes more.

Comet Hale-Bopp and meteor. Credit: Steve Ibbotson

This gives me the chance to show my favourite meteor photo.

It was taken by my friend Steve Ibbotson in 1997.

We were at a star party in Kelling Heath in Norfolk.

Steve took a photo of Comet Hale-Bopp as it hung brightly in the sky.

By chance he captured a shooting star alongside the comet’s tails.

It’s a lovely illustration of a meteor and its origin.

Thanks Steve!

Meteor Shower Dates

The table below shows the peak dates of the main meteor showers.

The names derive from the constellation from which the shooting stars appear to come.

The point they come from is called the radiant.

Meteor Shower Peak night Meteors/hour

Quadrantids Jan 4 / 5 100

Lyrids April 22/23 20

Perseids August 12/13 100

Orionids October 21/22 20

Leonids November 17/18 15

Geminids December 14/15 100

The Quadrantids can reach high numbers but only for a short time.

The best showers to observe are the Perseids in August and the Geminids in December.

However the most remarkable of annual showers is the Leonids.

They have an amazing history.

The showers have turned into meteor storms!

We’ll take acloser look at the Leonids in my next blog.

Leonids radiant. Credit: TMO/JPL/NASA

Observing meteors

Observing meteors is fun and doesn’t require any specialised equpiment.

Find a place outside as dark as possible unobstructed by buildings and trees.

Lay on a sunlounger, perhaps with a sleeping bag and gaze upwards.

Relax and watch for the falling stars!

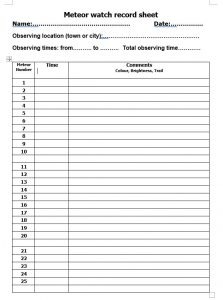

If you want to record a meteor shower, you need:

Red light torch (to preserve your night vision).

Watch, clock or smartphone to record the times.

A pen or pencil.

Recording sheet like the one below.

When you see a meteor, make a note of the time.

You might also record the speed – fast or slow.

And you might include any colour, brightness or train.

From your results you can calculate the hourly rate for the shower.

Meteor Brightness

You can estimate the brightness of meteors.

You compare the brightness of a meteor with the known brightness of stars.

In the magnitude scale, the lower the number, the brighter the star.

So here’s a rough guide to comparison magnitudes:

Mag +5: the dimmest stars visible

Mag +2: Pole Star

Mag 0: Vega, Saturn

Mag -1: Sirius (brightest star)

Mag -3: Jupiter, Mars

Mag -4: Venus (brightest planet)

Mag -6: Internmational Space Station

Mag – 12: Full Moon

For beginners in estimating magnitudes, it’s useful to have a star chart at hand.

Mark on the chart the magnitude of prominent stars.

Stellarium is a useful source of customised star charts.

When you see a meteor, compare it’s brightness with surrounding stars.

Decide which star it’s nearest in brightness to.

Then look up the magnitude of that star on your chart.

You can then record that as the brightness of the meteor.

It’s actually easier than it sounds!

Fireballs

A few meteors are exceptionally bright.

If one is brighter than planets Jupiter or Venus, it becomes a fireball.

That’s magnitude -4 or more.

As a rough rule of thumb, if it is reported in the media, it’s definitely a fireball.

Fireball

I have been lucky enough to see a good many fireballs over many years of observing the sky.

One lit up a car park as I walked with friends into a pub.

Another brightened our doorway as I returned home one night.

Both these fireballs were green and left trains that lasted several minutes.

At Oceanside in California I saw a daytime fireball.

It plummeted towards the ocean over an outdoor evangelist meeting.

A sign from God!

But the best all came in a single night back in 1998.

In an upcoming blog, I’ll recall my best stargazing night ever.

It was the Night of the Fireballs.

Watch this space!

The author: Dennis Ashton is a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society and a Wonderdome presenter.

Would you like to hear more Astronomy news?

Do you want to to find out about our upcoming public events?

Follow WonderDome Portable Planetarium on Twitter and Facebook or go to our web site wonderdome.co.uk