Asteroids

In the past, astronomers called them ‘vermin of the skies’.

They are the asteroids.

The name means ‘starlike’ but asteroids belong firmly in our Solar System.

They simply look like dim stars through a telescope.

But astronomers in the past derided them as vermin of the skies.

Their appearance could ruin a long-exposure research photograph.

We now regard them with greater respect.

They are original pieces of the Solar System which hold secrets about planet creation.

And in the future, asteroids may become a rich source of rare minerals to use here on Earth

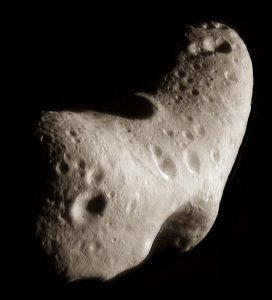

Asteroid Gaspra. Photo: NASA, Galileo project

But we also regard them with some trepidation.

In the past, asteroids have collided with Earth and caused mass extinctions.

Just ask a dinosaur how dangerous a rogue asteroid could be!

Origin

Asteroids are original fragments of the Solar System.

The Sun was made when a cloud of gas and dust collapsed under its own gravity.

The collapse heated hydrogen gas to over 10 million degrees.

Fusion reactions began and the Sun was born as a star.

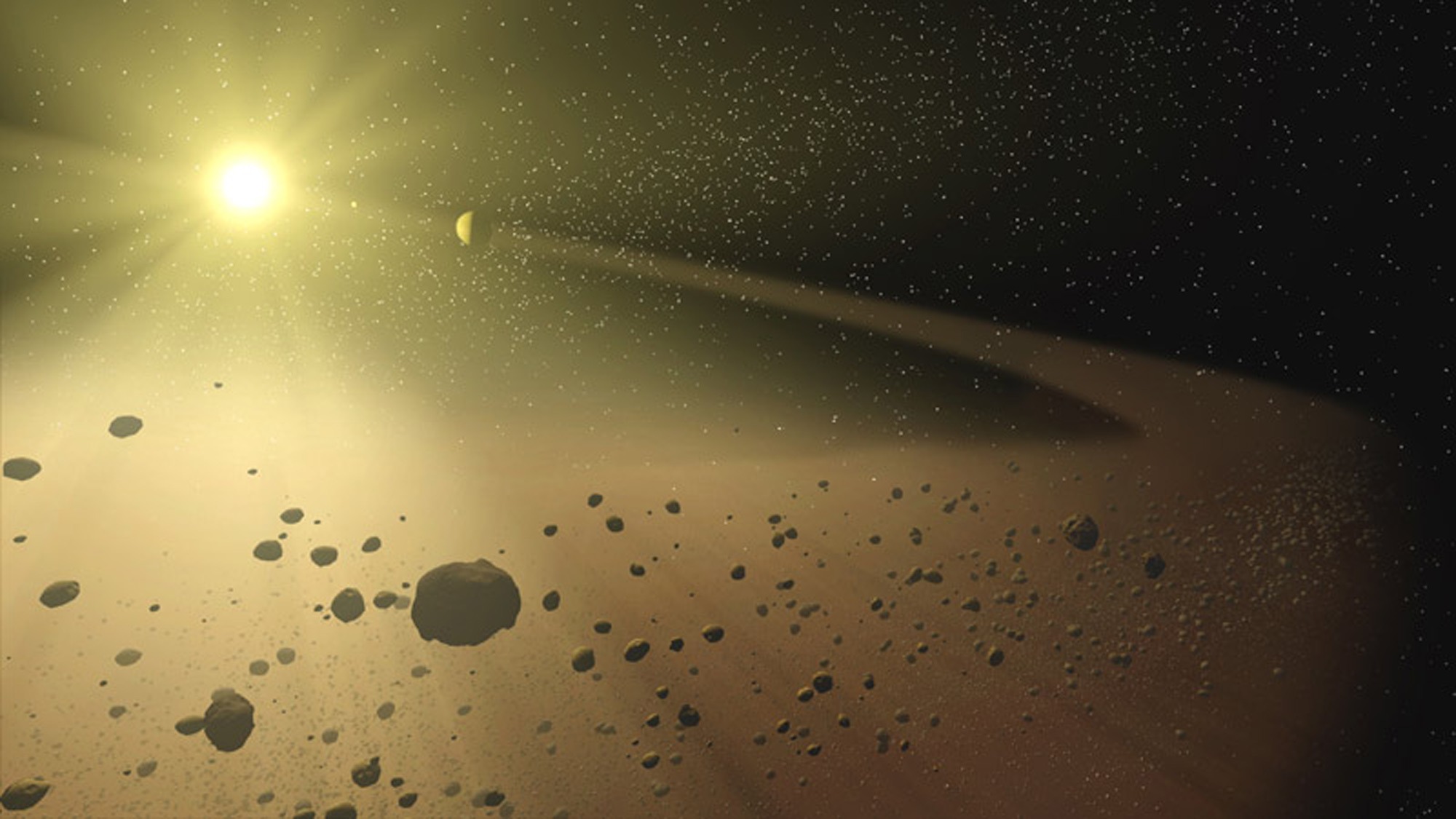

Solar System formation. Artwork: NASA

Over 99% of the gas and dust went into the Sun.

But some gas and dust remained and began to spin around the Sun in a disc of material.

Gravity collapsed parts of the disc.

Dust became pebbles, pebbles stuck together to form boulders.

Boulders crashed together to form asteroids and asteroids collided to make planets.

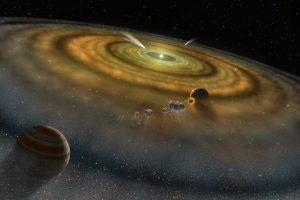

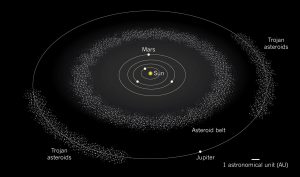

Asteroid belt. NASA artwork

But between Mars and Jupiter, the asteroids did not combine to create a planet.

The gravity of Jupiter prevented collisions.

The asteroids remained as rocks from as big as cars to the size of cities.

Now millions of asteroids orbit the Sun in the Asteroid Belt.

Orbits

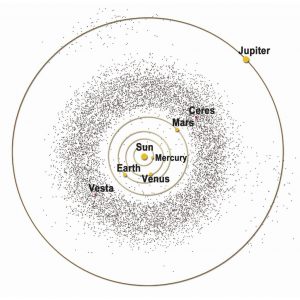

The main asteroid belt lies between Mars and Jupiter.

This is the area between the inner rocky planets and the outer gas giants.

Asteroid Belt. NASA artwork

The distance of the belt is from two to four times the distance of Earth from the Sun.

The belt is 225 million km wide (140 million miles).

Asteroids take around 5 years to orbit the Sun.

There are millions of asteroids in the belt, varying in size from a few metres across to kilometres.

The belt occupies a huge volume of space.

Although drawings suggest asteroids are close together, this is not the case.

Each asteroid is separated from its neighbours by 600,000 kilometres of empty space.

As a result, collisions of asteroids are rare, perhaps one every few million years.

Large asteroids

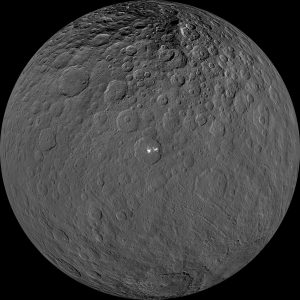

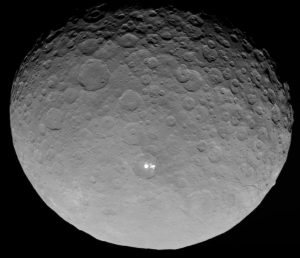

The largest asteroid is Ceres, some 945 km across (587 miles).

It has been categorised as a dwarf planet.

Ceres. Image: NASA

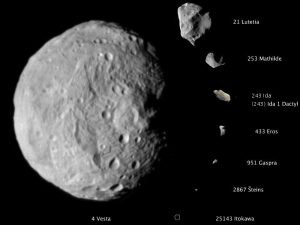

Next in size come Vesta at 525 km, Pallas at 512 km and Hygeia at around 400 km.

Together these four asteroids make up about 45% of the mass of the entire belt.

In all, we know of 23 asteroids which are more than 200 kilometres across.

Even though there are billions of asteroids, their total mass is quite small.

If all the asteroids, including the four big ones, came together, they would create a planet much smaller than our Moon.

Trojans

The vast majority of asteroids are in the main belt.

There are others with different orbits however.

Trojan asteroids. Credit: Nature

The Trojan asteroids lie in the orbit of Jupiter around the Sun.

They are found in front of and behind the giant planet.

Their orbits are stable because they congregate at two stable gravity points, the Lagrange points.

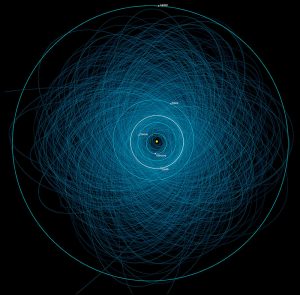

Near Earth Asteroids

These are the ones which raise concern for potentially catastrophic collisions with Earth.

Most of them come from the main asteroid belt.

Collisions or the gravitational effects of Jupiter knocked them out of orbit.

Tracks of Near Earth asteroids. Image: NASA/JPL/Caltech

Around 29,000 NEAs are known, 900 of which have diameters one kilometres across or more.

We’ll assess the dangers posed to earth by NEOs in a future blog.

Composition

Asteroids are basically made of stone and metal.

About 75% are carbon-rich and known as C-type asteroids.

The rest are either predominately silicate rock or nickel-iron, M- and S-type.

Most are solid but some smaller ones resemble piles of rubble.

All are dark, their surfaces reflect little of the sunlight that falls on them.

Space Missions

Twenty asteroids have been visited by spacecraft.

Their cameras have given us our first close-up views of these small worlds.

Some asteroids visited by spacecraft: NASA/JPL-Caltech/JAXA/ESA

The first encounter was made in 1991 by the Galileo spacecraft.

On its way to Saturn, it passed by Gaspra.

Asteroid Gaspra. Photo: NASA, Galileo project

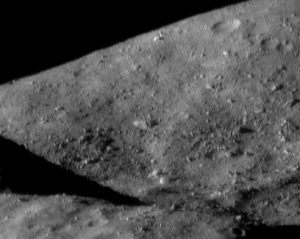

From 1998 to 2001, the NEAR Shoemaker probe visited Eros, a Near Earth Asteroid.

NEAR went into orbit around Eros then landed a probe on the asteroid.

Asteroid Eros. Photo: NEAR, NASA

NEAR landing site. NASA

Eros surface. NEAR/ NASA

In 2000 the Dawn mission visited the largest asteroid, dwarf planet Ceres.

It gave us wonderful closeup views of this cratered world.

Ceres. Image: NASA / JPL

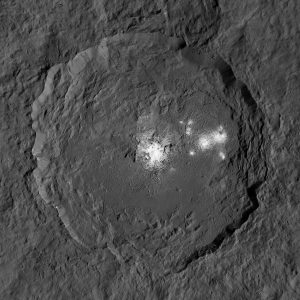

Standing out against the grey surface were two bright white spots.

They were inside a crater named Occator and Dawn’s cameras zoomed in on it.

Occator crater, Ceres. Image: NASA / JPL

The white spots seem to be made of sodium carbonate.

It is welling up from a brine layer beneath the icy surface.

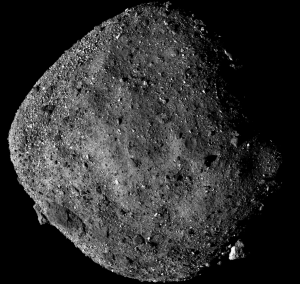

In December 2017, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx probe visited asteroid Bennu.

It took samples from the asteroid to return to Earth.

The samples should be here in autumn 2023.

Asteroid Bennu. Image: NASA OSIRIS-REx

The DART MIssion

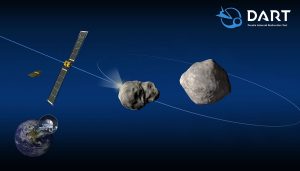

The latest spacecraft to visit an asteroid is the DART mission, launched by NASA in 2021.

Didymos is a double asteroid with a moon called Dimorphos.

Dawn’s mission was to test a way of protecting Earth from a future asteroid impact.

It would crash a probe into Dimorphos to see if the impact would alter its orbit.

DART Mission; NASA/Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab

We’ll report on the DART mission in a future blog.

Then we’ll consider the possibility and potential effects of an asteroid collision with Earth.

Vermin of the Skies?

Finally we return to the derogatory term given to the Solar Systems smallest members.

It is an unfair title.

Space missions have shown that asteroids are fascinating little worlds.

They still hold secrets which spacecraft may reveal in the future.

But that future also holds danger.

We’ll assess the hazards in a coming blog.

The author: Dennis Ashton is a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society and a Wonderdome presenter.

Would you like to hear more Astronomy news?

Do you want to to find out about our upcoming public events?

Follow WonderDome Portable Planetarium on Twitter and Facebook or go to our web site wonderdome.co.uk