Perseid Meteors.

August is one of the best months to see shooting stars.

This month sees the peak of one of the most reliable and spectacular meteor displays.

They are the Perseid Meteors.

What is a shooting star?

A shooting star is properly named a meteor.

A meteor is a piece of space dust which burns up in the atmosphere.

It looks like a falling star.

Well, that’s the simple explanation.

The truth is a bit more complex.

Each fragment of space dust is called a meteoroid.

This dust comes mainly from comets that occasionally enter the inner Solar System.

When that dust hits our earth’s atmosphere, it comes in at speed.

The combined speed of Earth in orbit and the speed of the dust gives collision speeds of thousands of miles an hour.

The Perseid meteors hit our atmosphere at around 36 miles per second.

That’s around 130,000 mph!

At such speeds, the space dust ionises gases in our atmosphere.

The passage of the particle strips electrons from atoms in the air.

This causes the gas to glow.

As the particle moves it creates a tiny tube of glowing gas, a streak of light in the sky.

It looks just like a shooting star.

The particle of dust burns away during its fiery descent.

It is completely burnt up between 50 and 80 miles high.

Meteors don’t hit the ground.

Space rocks which impact earth are much bigger particles.

When they hit the ground, they become meteorites.

That’s a subject for another blog.

So no need to wear a hard hat if you go out meteor watching!

Meteor Showers

When comets move through the inner Solar System, they leave a trail of dust behind them.

Occasionally our Earth crashes through a trail of comet dust.

Then we see lots of meteors in a short time.

It is a meteor shower.

The term is a bit misleading.

It’s not like a shower of raindrops.

At their peak, meteor showers may show one shooting star every minute or two.

Origin of the Perseids

The Perseid dust comes from Comet Swift-Tuttle.

It was discovered independently by Lewis Swift and Horace Tuttle in 1862.

The comet orbits the Sun every 133 years.

It last returned to the inner Solar System in 1992.

It’s due back in 2126.

So you’ll have to wait a while to see it again!

The comet nucleus, a dirty iceberg, is around 25 miles across.

As the comet sweeps around the Sun, the ice evaporates.

The actual process is called sublimation, changing directly from solid to gas.

The gas makes a characteristic comet tail.

It carries with it particles of surface dust.

These heavier particles form a separate tail.

The two tails were well seen in the passage of Comet Hale-Bopp in 1997.

Comet Hale-Bopp, 1997

Credits: E. Kolmhofer, H. Raab; Johannes-Kepler-Observatory, Linz, Austria

In this image, the gas tail is blue whilst the dust tail is brighter and yellowish.

As the Earth orbits the Sun, it encounters the Swift-Tuttle dust in the middle of August.

So we have a regular annual meteor shower.

Why Perseids?

The stream of meteor dust is quite narrow.

When we crash into it, the meteors seem to come from just one small area of the sky.

For our August display, the area lies in the constellation Perseus.

That small area that the shooting stars emanate from is called the radiant.

The Perseids radiant at midnight on Aug 12-13. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

When to look.

We pass through the meteoroid trail between July 17th and August 24th.

Shooting stars will be seen on any clear night between these dates.

We encounter the thickest dust on the night of August 12 to 13th.

We may see around 100 meteors an hour, more than one a minute.

There is also the possibility of a mini-peak on the night of August 11th to 12th.

Then we may hit a separate filament of dust.

In 2023, the Moon is a slim crescent.

This is good for meteor watching, as its light will not blot out the fainter shooting stars.

The radiant of the shower is above the horizon as soon as the sky goes dark.

So you can begin to look for shooting stars as soon as it goes dark.

However most are seen after midnight and into the early hours.

If you can, stay up all night!

OK, that may a bit extreme.

If you want to see most meteors in a shorter time, get up early.

The pre-dawn hours usually see the peak numbers.

Where to look.

As the sky darkens, Perseus is in the east.

That’s where the early meteors will come from.

But the Perseids will fly to all directions in the sky.

Just choose the darkest part of your night sky and look there.

Over the years, I have found that many Perseids pass through the Summer Triangle.

The triangle is made up of the stars Vega, Deneb and Altair.

It dominates the sky looking south.

Summer Triangle, Stellarium

Wherever you look, you’ll miss some Perseids but they are so plentiful you’ll catch some too.

Great balls of fire!

Perseid meteors are fast and bright.

Sometimes the comet particles are big enough to give shooting stars so bright they become fireballs.

I have seen fireballs that light up the ground.

You’ll know a fireball when you see one!

A meteor watch.

If you would like to do some original science, you can carry out a meteor watch.

You will need:

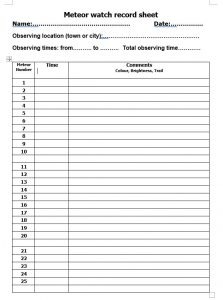

Copies of our table (25 meteors per sheet).

Something to rest the paper on.

A pen or pencil.

A time piece, watch or clock.

A clear (ish) sky.

Lots of patience

Wrap up warm. Summer nights can still be cold.

Take with you a hot drink and perhaps a device with earbuds to listen to music.

A torch is useful, particularly if you cover it in red plastic or cellophane.

This means you can see without ruining your night vision.

Make yourself comfortable by reclining so that you can see the sky.

A sun lounger makes an ideal meteor watching bed.

Meteor recording

First fill in the details at the top of the form.

Then lie back and watch for shooting stars!

When you see one, record the time to the nearest minute.

In the comments column you can record the colour of that meteor.

You could also estimate its brightness.

For example, faint….bright….very bright…..fireball.

Some bright meteors leave a trail of light that lasts a few seconds or sometimes minutes.

That’s worth recording too.

If you know your constellations, you might record where you saw each shooting star.

When you’ve finished your watch, record the time and total observing times.

I would be interested to see your results.

Please send them to Wonderdome and I’ll feature them in a future blog.

I wish you clear skies and lots of falling stars!

The author: Dennis Ashton is a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society and a Wonderdome presenter.

Would you like to hear more Astronomy news?

Do you want to to find out about our upcoming public events?

Follow WonderDome Portable Planetarium on Twitter and Facebook or go to our web site wonderdome.co.uk